In 1635, María, a slave woman from the Indian sub-continent living in the Spanish-controlled Philippine Islands, enters the historical record. We know that women as well as men were involved in forced movements like María’s around the region but historical documentation about their lives is rarely available.

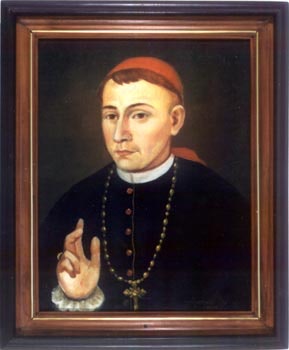

María was owned by an artilleryman named Francisco de Nava who was then living in Manila. In 1635, the city’s archbishop, Don Hernando Guerrero, began an investigation into, in the words of the contemporary documents, “illicit communication” between the two.

Nava explained that they had an understanding. “He had brought María from India, saying that he was going to marry her, as he had taken her while she was a maiden”.

This was, in his eyes at least, a contract for her virginity: María would gain a respectable marriage in exchange for her sexual labour.

A slave’s autonomy

However, the evidence surrounding this case suggests María had other ideas. She “left the house, going to that of Juan de Aller, a kinsman of Doña Maria de Francia, wife of Don Pedro de Corcuera, whom she asked to buy her.”

A contemporary report noted that “the slave girl said that she preferred to belong to another” than to be Nava’s wife.

Maria de Francia, an influential woman who was the wife of the governor’s nephew, “became fond of her” and sought to buy María from Nava, with support from the archbishop.

Female slaves such as María were vulnerable to the sexual expectations of their masters and as migrants, they generally had few familial or other social networks to assist or protect them.

How did María attract the attention and sympathy of powerful local citizens to assist her? She had managed to engage ecclesiastical authorities and elite women in her plight, who were prepared to step in, in order to instil Catholic moral values.

The sexual behaviour of women and men in Manila was of great concern to Spanish secular and ecclesiastical officials. The city was a known trading centre for slaves but Spanish authorities were anxious about the “many offenses to God” that took place between female slaves, in particular, and men in the city.

In 1608, King Felipe III had outlawed the “evil” of the passage of female slaves aboard vessels, but the practice continued. In November 1635, the governor, Don Sebastian Hurtado de Corcuera, once again complained about the “great license and looseness of life” in Manila.

María’s case may thus have offered authorities an opportunity to discipline the wider population and reinforce moral expectations. They were willing to recognise a slave woman’s capacity to resist sexual exploitation, although not, it seems, a right to freedom from slavery itself.

A tragedy

At María’s departure, Nava was reportedly “so beside himself over the loss of the said slave that he refused to sell her at any price, saying that he wished, on the contrary, to marry her.”

But there were other stories circulating that complicated his narrative. The governor, for example, reported that Nava “had said the year before that he had been married in Nueva España.” Could his marrying María be even legally possible?

Still, Nava went to de Francia’s house, “to request that they should give him the slave,” whereupon he was beaten and placed in the stocks.

His reaction to the loss of María was perceived by onlookers as excessive, and shortly afterwards, an order was given that he should be treated as if he were mad.

On Sunday, 8 August 1635, at three in the afternoon, María was passing by in the street in a carriage with her new mistress. Nava approached them, asking María if she recognised him as her master.

Interestingly, one account provides another hint of a possible assertion of autonomy in María’s actions: “The slave answered him with some independence”, it was reported. But María’s precise words were not considered worthy of note for the historical record.

The encounter ended tragically for María. “Blind with anger,” Nava “drew his dagger in the middle of the street and killed her by stabbing her, before anyone could prevent it.”

Nava was condemned to death. On 6 September 1635 he was executed on gallows raised at the site where María had been killed, in front of the San Agustin Church.

María’s agency

This is not a celebratory history, for María’s life ended abruptly. We don’t know what María looked like or how she felt about her plight except through her actions as they were recorded by others. What we do know about her comes from documents created by Nava’s crime.

But these documents provide small insights into the experiences of displaced and marginal women who are typically among the most silent in the archives.

They reveal María’s forms of agency and resistance — not only in her access to support mechanisms among the powerful Catholic elite of colonial Manila, but also in her most basic impulse to refuse to accept her situation and to seek a better life within the limited choices before her.![]()