Lester Tenney, an Army tank commander who survived the Bataan Death March and spent his life campaigning for a Japanese apology, has died aged 96.

When his ordeal as a prisoner of war (POW) was over, he learned that his wife had remarried, believing him dead. Although he suffered greatly with post-traumatic stress and ‘survivor’s guilt’, he rebuilt his life with a new marriage and a successful career in the academic and business worlds.

He also waged a relentless and ultimately successful campaign to win apologies from Japanese leaders for their nation’s brutality.

“I’ve learned to forgive,” Mr Tenney said during the 70th anniversary of the march in 2012, “but I will never forget.”

His memories of the infamous eight-day trek and of the three years he was forced to work in a coal mine were detailed in a memoir called My Hitch in Hell.

Mr Tenney, who lived in Carlsbad, California, died on Friday, his grandson David Levi has announced.

Born in Chicago in 1920, Lester Irwin Tenney joined the Army in 1940, and was posted to the Philippines.

In December 1941, just weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese forces invaded the Philippines. Unprepared and outnumbered Allied forces — about 15,000 Americans and 60,000 Filipinos — withdrew to the Bataan peninsula.

There they put up a brave resistance for more than three months before they ran out of food and ammunition. Major General Edward King ordered them to surrender and their fortunes went from bad to worse as the Japanese ordered them to march to their distant prison camps.

For the first four days of the forced march, the prisoners were denied any food or water — despite temperatures soaring well over 100 degrees.

Those who succumbed to exhaustion were stabbed with bayonets, shot or beheaded. “If you fell down, you died,” Mr Tenney said. “If you stopped walking, you died.

“We had no food or water. The temperature was about 106, 108 degrees. We all had malaria, dysentery.”

About halfway through the march, a Japanese officer on horseback slashed at Mr Tenney’s shoulder with a sword. Two brothers in arms held him up while a medic stitched the wound. “If they let me fall, I would’ve been dead,” he said.

By the time he and the surviving prisoners staggered into the Japanese camps, thousands had perished along the way. By some estimates of the death toll, the dead, laid end to end, could have covered the entire route.

“It was awful,” Mr Tenney said. “It was inhumane. It was barbaric.”

Despite arriving at the camp as a physical wreck, Mr Tenney was not a man to lie down quietly. He soon managed to escape and holed up in the jungle. However, he was captured and crammed onto a ship bound for Japan, where gruelling slave labour in a coal mine awaited him.

There he was forced to dig for 12 hours a day, seven days a week, surviving on three small bowls of rice and a little water daily. He was often beaten by Japanese guards or employees of the mine company.

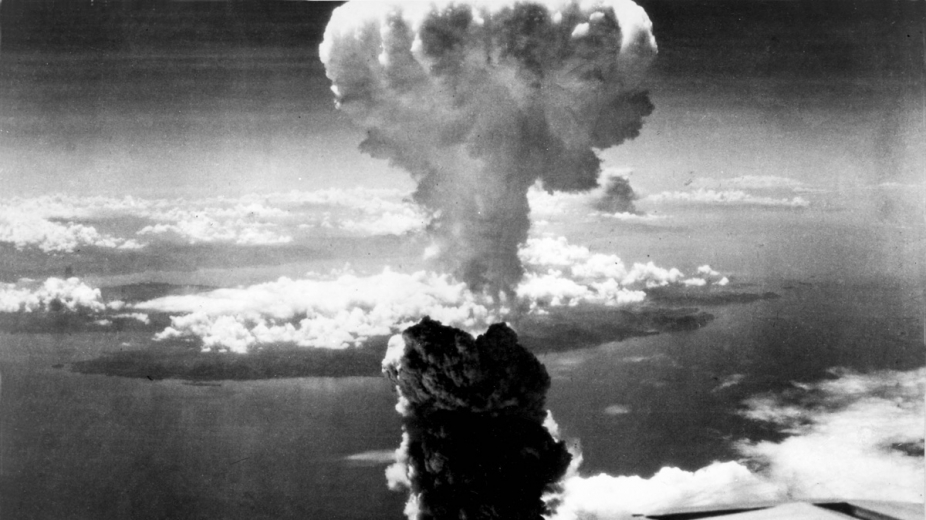

He was in the prison camp at Omuta, just across the bay from Nagasaki, when he witnessed the second atomic bomb being dropped in August 1945, paving the way for Japan’s surrender.

Mr Tenney came home with just eight teeth left — the rest had been knocked out by his brutal captors. On his return, and finding his wife remarried, his life seemed doomed to spiral out of control. “I wasn’t so proud of being a prisoner of war,” he said.

However, demonstrating the same spirit that had seen him survive the war, he set to rebuilding his life. In 1959, he met Betty Levi, and they married a year later.

Mr Tenney then earned business degrees from San Diego State University and USC and became a college professor. In 1966, he and his wife moved to Tempe, where he taught at Arizona State and started a company, University Research Associates, which provided financial and retirement planning for US companies.

After he retired, and his memoir was published, Mr Tenney started to heap pressure on the Japanese authorities to acknowledge what had happened during the war.

In 1999, he and other POWs sued five Japanese mining companies for recompense for their slave labour. A federal judge dismissed the suit, citing a 1951 peace treaty between Japan and the US.

But Mr Tenney was not a man to give up easily.

Return to Japan

He then started travelling to Japan to educate schoolchildren whose history books glossed over the sins of their forefathers and didn’t mention the Bataan march at all.

He also became a familiar face on television and in the press, tirelessly raising awareness of what had been done to him and his brothers in arms.

In 2009, as national commander of the Defenders of Bataan & Corregidor, he invited Japanese Ambassador Ichiro Fujisaki to the group’s annual convention, where he finally apologised sincerely on behalf of his country.

A year later, Mr Tenney went to Tokyo as part of the first American delegation to Japan’s Peace, Friendship & Exchange Initiative, a gesture of reconciliation from the Japanese government to its wartime prisoners.

In 2015, Tenney was invited to Washington to watch Shinzo Abe, Japan’s prime minister, give a speech to Congress. Along with other veterans, he was profoundly unimpressed by Mr Abe’s apparent lack of unconditional contrition.

But later that day, at a gala outside the Smithsonian Institution’s Freer Gallery, Mr Abe voluntarily apologised to Mr Tenney face to face.

A fighter until the end

Still, the determined old soldier had one more battle to fight — getting an apology from the mining companies who had enslaved him, and very nearly worked him to death.

Only last month, just weeks before his death, a letter arrived from the Mitsubishi Materials Corporation. Although this wasn’t the company that had enslaved him directly, Mr Tenney was grateful nonetheless. To his last breath, he remained hopeful that the other companies involved in the vile treatment of Allied POWs would one day follow suit.

He was also passionately concerned for the wellbeing of latter-day soldiers too; throughout his old age he would put together ‘Care Packages From Home’ for men and women serving in Afghanistan and Iraq.

In addition to his son Glenn, from his second marriage, which ended in divorce, Mr Tenney is survived by his third wife, Betty, his stepsons Edward and Donald Levi, and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Glenn accompanied his father on many trips to Japan, including a visit to the site of the coal mine where his father was enslaved. He recalled this weekend how his father “was in tears” when he picked up a stray piece of coal that “brought back all the memories”.

RIP sir. We will never forget.